Evidence is mounting that megalodon could have been warm-blooded, unlike most modern sharks, hinting at how it grew to be so big and also why it went extinct

By Sofia Quaglia

26 June 2023

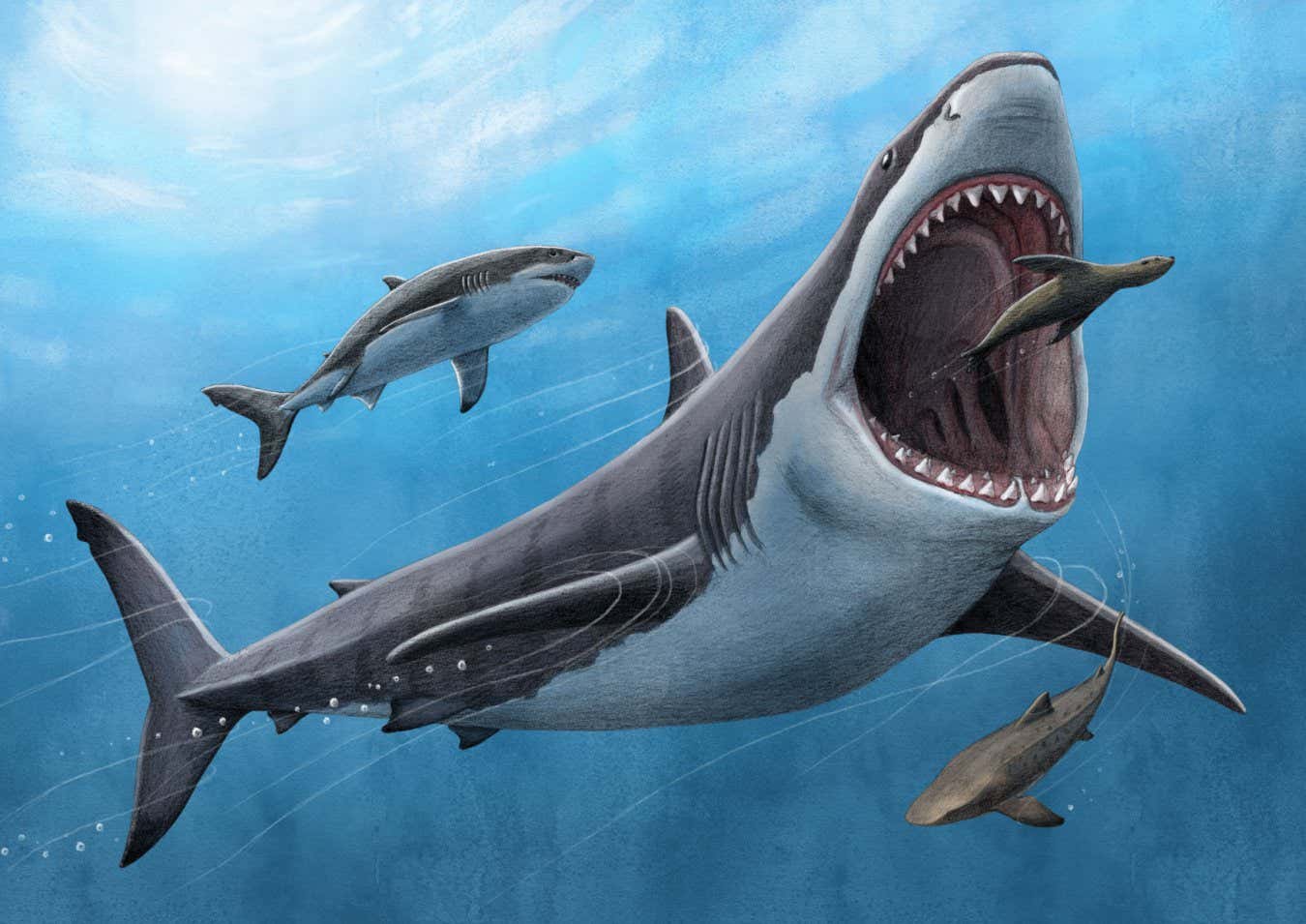

An artist’s impression of megalodon

Alex Boersma/PNAS

The iconic 15-metre-long megatooth shark known as megalodon – who reigned the world’s waters up to 3.6 million years ago – was warm-blooded in some of its body parts, according to a chemical analysis of fossilised megalodon teeth. This evolutionary adaptation helps explain how the fierce apex predator managed to get so gigantic and why it went extinct.

Robert Eagle at the University of California, Los Angeles, and his colleagues analysed 29 gigantic, fossilised megalodon teeth from the Pliocene and Miocene epochs, from the North Pacific and North Atlantic Oceans.

They looked at how two isotopes, carbon-13 and oxygen-18, found in the shark’s preserved teeth bond together, knowing from other research that the more clumped they are, the warmer the body.

Advertisement

Their analysis suggested the megalodon’s overall, average body temperature was about 27˚C (80.6˚F). That is around 7˚C warmer than the oceans it was swimming in. Warm-bloodedness is rare in sharks, with only five out of 500 modern-day species having the adaptation.

Like those six extant sharks, the megalodon was also probably just regionally endothermic – meaning it made its own heat from metabolism only in certain parts of its body and was still colder than warm-blooded marine mammals, says Eagle.

Not only was the shark probably warming its brain, eyes and digestive system, but as its body temperature was about 5°C higher than modern-day warm-blooded sharks, that leaves the possibility that it could have been capable of mammal-like full-body endothermy, says Lucas Legendre at the University of Texas at Austin. But that is unlikely, he says.